F-words is a place on our blog where we share opinions on topics we care about.

The messages presented to us as we move through public spaces have traditionally conformed to certain semiotic norms and clearly demarcated spaces. A revolving tram shelter ad from a travel agent tells me I need a holiday on a tropical beach; a glowing sign suspended above a shop window claims I won’t find better dumplings; spray-painted nicknames and slogans jostle for space on a laneway wall.

These are just a few of the many messages we’re exposed to every day. The difference I want to focus on is that first two examples are messages in public space that are paid for by organisations offering a service or product. The third is graffiti, an unsanctioned act of self expression made on private property. Although graffiti is judged by many as an act of vandalism, the gap between it and its distant corporate cousin, advertising, has narrowed in recent years. Advertisers who seek to enter our consciousness laterally through the back door, often flirt with concepts that underlie graffiti – provocation, irreverence, anti-establishment, situationalism.

Before and after, artist Mathieu Tremblin, 2017

Developments in printing and screen technology now allow commercial messages to appear on many more surfaces and locations in public spaces, which raises questions about their ownership and democratic use.

Just as advertisers have a greater choice of rental spaces to tout their message, individuals and activist groups have sprung up to subvert them in the name of making public spaces more democratic. Rather than using spray cans and stencils ‘subvertisers’ often use the advertiser’s tools against them to challenge what they see as ‘corporate graffiti’.

In March this year, Subvertisers International invited Melburnians to take creative action against advertising and consumerism. Their Meetup page stated: ‘Commercial advertising invades our spaces and all forms of media in order to influence our behaviours and serve corporate interests. We believe that commercial advertising dominates the culture and gives power to the wealthy, endangering democratic processes.’

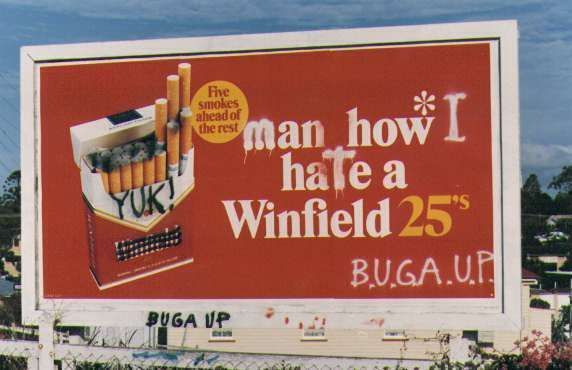

Winfield billboard ad, Billboard Utilising Graffitists Against Unhealthy Promotions (B.U.G.A.U.P.), Australia 1980

Replaced billboard ad, Subvertisers International

Subvertiser tactics are based on a long tradition of altering the meaning of commercial messages but these days the means are more sophisticated.

In June, self proclaimed pastafarian John McKenzie made the headlines after he was spotted applying posters celebrating pasta to Melbourne’s mysterious Jesus bikes. For years these bikes have carried signs with painted religious messages and can be seen locked in different locations across the city. Adorning bikes with messages is not new, but in a classic example of corporate graffiti, Mr McKenzie’s bold posters served to promote his business while poking fun at religious extremism. In an interview with The Age he said ‘I think the city should be free of anybody’s ideological messages taking up bike space.’

Jesus bike, Elizabeth Street, Melbourne 2017

Last month a new group calling itself TramClean pulled off a stunt that amazed tram operators, advisers and consumer advocates alike. Wearing hi-vis vests bearing an ‘Adhell’ logo (a play on Adshel) and a purposeful look, TramClean teams began peeling away ads from the sides of trams and from tram stops. Onlookers assumed they were professionals. A statement from the TramClean website states their aim: ‘As citizens we have not consented to having our public space invaded by the advertising of corporate entities interested only in generating profit. Public space, if marked with anything, should be available to the people for community enrichment and the display of arts and culture.’

From the TramClean website, Melbourne 2017

Public comment on news websites covering these activities tends to be polarised: those who laud the benefits of advertising – greater choice of products and services, economic growth, lower costs – and those who resent being a captive audience for unsolicited messages. As the battle to occupy space in the public mind continues, I asked four Fentonites whether they think these new forms of creative disruption help to make public spaces more democratic or whether they are simply sophisticated forms of vandalism:

Melanie Wilkinson, Fenton CEO

‘It’s complicated and depends on the specific issue, but in general the law would define the actions of organisations such as TramClean as vandalism. Although trams in Melbourne are ‘public’ transport they are operated by private companies under licence and that licence includes the ability to use the infrastructure to earn income from advertising. This income does help keep the cost of the transport down so if you don’t want the advertising you should exercise your legal democratic rights and lobby for removing it and increasing the fares for consumers to cover the difference.

There is great creativity in some of these stunts and I certainly agree with the philosophy that genuine public space should (and I believe is) available for display of arts and culture. I would also note that in many cases such as the changing of advertising messages on billboards the actions of the activist has given the advertiser more publicity and may in the long term backfire.’

Aaron Williams, Design Director

‘I’m all for creative execution, whether it’s part of a communication campaign, activists cleverly altering advertising or beautiful street art. There will always be people reacting against the proliferation of advertising in society and creative agencies pushing the limits to create new mediums to expose their client’s message.

When perceived cleverness actually breaches the law it’s a real problem and this can be said for both sides.

Public transport has the right to advertise to raise revenue and TramClean’s actions were pure vandalism. The recent advertisement/mural for the movie ‘Mother’ that was painted over a 20 year old mural in a Sydney ‘heritage area’ without council approval is also terrible and will be an interesting benchmark for this new approach to advertising if it leads to prosecution.’

Alexandra Haddon, Account Manager

‘The recent trends in Subvertising, Art in Ad Places etc forces advertisers to be more creative. Outdoor advertising is frequently becoming more like native online advertising. That is, trying to blend in with organic content. The murals Aaron mentioned are an example of this. On the weekend I noticed an ad for the movie ‘IT’ near my house in the form of a mural – very spooky but effective. (As far as I’m aware they didn’t paint over a heritage site.)

Sorayia Noorani, Senior Consultant

‘We are exposed to advertising almost everywhere we go that we don’t often think about the impact that it’s having on our behaviours and decision-making. So while I don’t agree with subvertertisers breaking the law, I think it’s an interesting reminder that we aren’t in complete control of our attitudes and decision-making when it comes to the products and services we buy.

I read an article recently that said if advertising didn’t work, Coca-Cola wouldn’t spend over $4 billion every year on advertising just for brand awareness – people know what Coke is. This feeds in to a deeper argument about good corporate social responsibility when it comes to advertising in public spaces. So while I wouldn’t condone vandalism, I hope that it encourages private companies with public ad space to think harder about the types of products and services they are willing to spruik and whether it’s worth the detrimental impact on public health.’

By Alan Fitzpatrick